CLOs: Lessons From The Past

In recent weeks we’ve seen significant sell-offs across all asset classes as investors have been scrambling for liquidity. With most of Europe and the US effectively in lockdown, a recession looks to be inevitable and the question is what this will do to corporates’ ability to service and refinance their outstanding debt, especially for those in the sub-investment grade space.

Comparisons to the sovereign debt crisis of 2011-2013 or even the global financial crisis of 2008 are easily made, but there are some significant differences here. Not least of these is the reason for the economic slowdown. COVID-19 has disrupted everyday life globally and will result in a sharp slowdown of earnings in many sectors. Think of the hospitality sectors closing their doors for weeks if not months, retailers that have seen high street footfall plummet, aviation where traffic has tumbled, companies relying on higher oil prices, the list goes on. Many of these corporates have got a lot of debt outstanding and leverage is at all-time highs. However, interest coverage is also very high (helped by very low interest rates) and equity checks in M&A transactions have been substantial, so the willingness to walk away from these firms will be limited in our view. The lack of covenants (other than those on revolving credit facilities) will take some immediate pressure away from lenders breathing down CFOs’ necks. The spread tightening in 2019 and early 2020 resulted in a lot of margin compressions, but more importantly maturity extensions.

Nevertheless, there will be casualties and defaults rates are extremely unlikely to remain at all-time lows. We don’t expect default rates to rise straight away to the worst levels seen during the financial crisis, but we would expect a pick-up towards the end of Q2 or in the second half of the year. If a company is in financial distress, lenders (in this case the CLO managers) won’t be foreclosing straight away. We would expect lenders, as we saw in 2009-2011, to work with companies to get them back on track, unless there’s no outlook for things to turn around. Lenders can consider things like coupon reductions, debt restructurings (debt for equity swaps), maturity extensions, payment holidays and Payment-in-Kind notes, for example. And distress does not always have to result in lenders taking the keys of the business and putting new management in, assuming that the private equity sponsors are not willing to put more equity into the business.

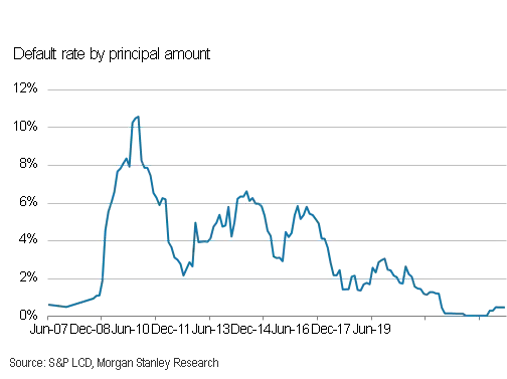

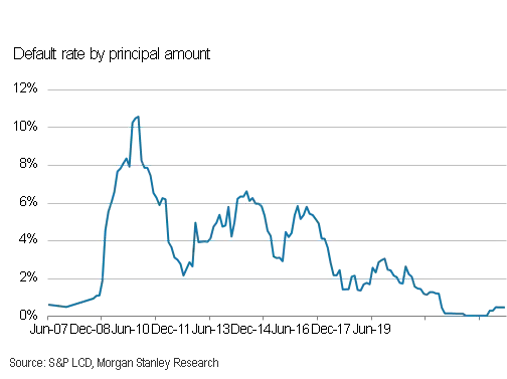

Morgan Stanley has given a nice overview today of where historic default rates were for European leveraged loans, and we can see that in 2009 default rates peaked at just over 10%. We know that historically the recovery rates on these senior secured loans have been in the range of 70-75%, but it’s widely assumed that due to the lack of covenants this recovery rate is more likely to be around 60%.

Defaults are not the only thing impacting the cash flows of CLOs. Downgrades of the underlying collateral (from the average single-B rating) to CCC+ or lower levels can also impact cash flow diversions from the equity notes to senior noteholders. A CLO will typically have a 7.5% CCC limit, and any assets above this levels will have to be carried at market value for the ‘over-collateralisation’ test (OC test), which is essentially a risk-adjusted coverage test designed to protect rated noteholders.

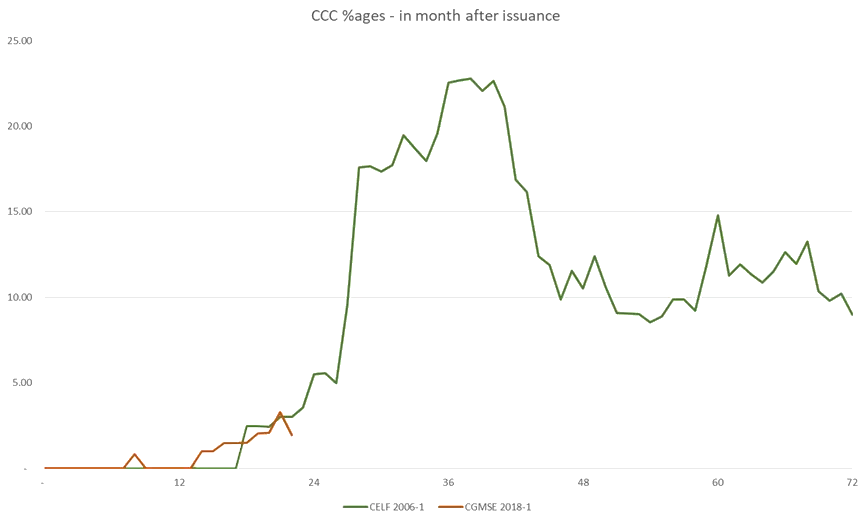

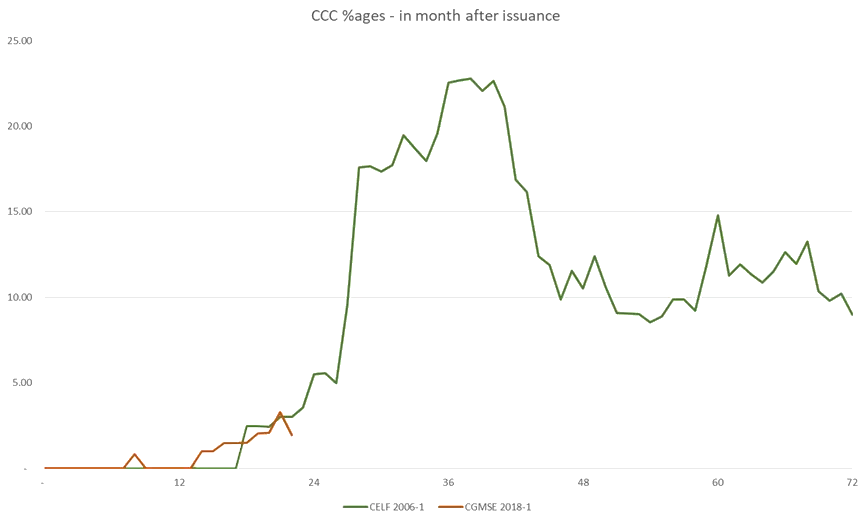

Let’s take a look at a 2018 CLO managed by Carlyle, which has managed CLOs since the early 2000s. CGMSE 2018-1 was issued in October 2018 and currently has 4.1% of headroom on their most junior OC test (just below the single-Bs), before a cash flow diversion from equity to AAA would be triggered (which was the case for over two-thirds of CLOs during the financial crisis). For this test to breach – which assumes the CCC assets would sell down to 50 cents from the mid-to-high 70s valuations we’re seeing today – we would need to see an increase from current CCCs at 1.96% to over 15% in a very short period of time. For BB cash flows to be deferred, we would need to see a sudden increase to around 20%. This doesn’t necessarily mean that the manager doesn’t add value (don’t forget that part of their fees are paid junior to these OC tests so clearly are aligned). CLO managers can sell CCC rated assets, but they can also buy additional collateral below par (the deal mentioned can for example re-invest until Oct 2022, and there are plenty of high quality names trading at what look like attractive levels) to boost the protection for the rated noteholders and increase the headroom on these OC tests. That said, it is very likely we will see downgrades to CCC pick up in Q2. There are plenty of B-/B3 rated names already on ‘watch negative’ and a slowdown of earnings can trigger the rating agencies to downgrade these.

Historically the median CCC-and-lower bucket in European CLOs has peaked at 10-12%, but there have been plenty of deals that had CCCs at 15-20% or higher. Morgan Stanley today refers to research from Fitch, which has seen cumulative historic losses of 0.05% for all CLOs it has rated (these focused on junior rated tranches). But let’s stick with Carlyle as a manager and compare the deal mentioned above to one of the deals the firm did in 2006 (CELF 2006-1), which performed significantly worse than its peers – at the peak it had 23% of CCC-and-lower rated assets, and 6% of outstanding defaults in the pool. But even this deal which had CCCs peaking at around 22.5% fully repaid all rated note holders at par (the last one in 2018).

Source: Intex, investor reports, TwentyFour, 19 March 2020

Source: Intex, investor reports, TwentyFour, 19 March 2020

Central bank and government support globally is now a lot more timely than it was in 2008, and we don’t expect defaults or even leveraged loan downgrades to be as severe as we have seen from the worst crisis of modern history. However, sometimes it is valuable to look back and see how bad things got and how the market recovered. We certainly have been using this historical experience as an input for our stress testing models for a long time, and it is one factor that can make us feel more comfortable holding CLOs through such periods of market volatility.

Comparisons to the sovereign debt crisis of 2011-2013 or even the global financial crisis of 2008 are easily made, but there are some significant differences here. Not least of these is the reason for the economic slowdown. COVID-19 has disrupted everyday life globally and will result in a sharp slowdown of earnings in many sectors. Think of the hospitality sectors closing their doors for weeks if not months, retailers that have seen high street footfall plummet, aviation where traffic has tumbled, companies relying on higher oil prices, the list goes on. Many of these corporates have got a lot of debt outstanding and leverage is at all-time highs. However, interest coverage is also very high (helped by very low interest rates) and equity checks in M&A transactions have been substantial, so the willingness to walk away from these firms will be limited in our view. The lack of covenants (other than those on revolving credit facilities) will take some immediate pressure away from lenders breathing down CFOs’ necks. The spread tightening in 2019 and early 2020 resulted in a lot of margin compressions, but more importantly maturity extensions.

Nevertheless, there will be casualties and defaults rates are extremely unlikely to remain at all-time lows. We don’t expect default rates to rise straight away to the worst levels seen during the financial crisis, but we would expect a pick-up towards the end of Q2 or in the second half of the year. If a company is in financial distress, lenders (in this case the CLO managers) won’t be foreclosing straight away. We would expect lenders, as we saw in 2009-2011, to work with companies to get them back on track, unless there’s no outlook for things to turn around. Lenders can consider things like coupon reductions, debt restructurings (debt for equity swaps), maturity extensions, payment holidays and Payment-in-Kind notes, for example. And distress does not always have to result in lenders taking the keys of the business and putting new management in, assuming that the private equity sponsors are not willing to put more equity into the business.

Morgan Stanley has given a nice overview today of where historic default rates were for European leveraged loans, and we can see that in 2009 default rates peaked at just over 10%. We know that historically the recovery rates on these senior secured loans have been in the range of 70-75%, but it’s widely assumed that due to the lack of covenants this recovery rate is more likely to be around 60%.

Defaults are not the only thing impacting the cash flows of CLOs. Downgrades of the underlying collateral (from the average single-B rating) to CCC+ or lower levels can also impact cash flow diversions from the equity notes to senior noteholders. A CLO will typically have a 7.5% CCC limit, and any assets above this levels will have to be carried at market value for the ‘over-collateralisation’ test (OC test), which is essentially a risk-adjusted coverage test designed to protect rated noteholders.

Let’s take a look at a 2018 CLO managed by Carlyle, which has managed CLOs since the early 2000s. CGMSE 2018-1 was issued in October 2018 and currently has 4.1% of headroom on their most junior OC test (just below the single-Bs), before a cash flow diversion from equity to AAA would be triggered (which was the case for over two-thirds of CLOs during the financial crisis). For this test to breach – which assumes the CCC assets would sell down to 50 cents from the mid-to-high 70s valuations we’re seeing today – we would need to see an increase from current CCCs at 1.96% to over 15% in a very short period of time. For BB cash flows to be deferred, we would need to see a sudden increase to around 20%. This doesn’t necessarily mean that the manager doesn’t add value (don’t forget that part of their fees are paid junior to these OC tests so clearly are aligned). CLO managers can sell CCC rated assets, but they can also buy additional collateral below par (the deal mentioned can for example re-invest until Oct 2022, and there are plenty of high quality names trading at what look like attractive levels) to boost the protection for the rated noteholders and increase the headroom on these OC tests. That said, it is very likely we will see downgrades to CCC pick up in Q2. There are plenty of B-/B3 rated names already on ‘watch negative’ and a slowdown of earnings can trigger the rating agencies to downgrade these.

Historically the median CCC-and-lower bucket in European CLOs has peaked at 10-12%, but there have been plenty of deals that had CCCs at 15-20% or higher. Morgan Stanley today refers to research from Fitch, which has seen cumulative historic losses of 0.05% for all CLOs it has rated (these focused on junior rated tranches). But let’s stick with Carlyle as a manager and compare the deal mentioned above to one of the deals the firm did in 2006 (CELF 2006-1), which performed significantly worse than its peers – at the peak it had 23% of CCC-and-lower rated assets, and 6% of outstanding defaults in the pool. But even this deal which had CCCs peaking at around 22.5% fully repaid all rated note holders at par (the last one in 2018).

Source: Intex, investor reports, TwentyFour, 19 March 2020

Source: Intex, investor reports, TwentyFour, 19 March 2020Central bank and government support globally is now a lot more timely than it was in 2008, and we don’t expect defaults or even leveraged loan downgrades to be as severe as we have seen from the worst crisis of modern history. However, sometimes it is valuable to look back and see how bad things got and how the market recovered. We certainly have been using this historical experience as an input for our stress testing models for a long time, and it is one factor that can make us feel more comfortable holding CLOs through such periods of market volatility.