Labour market the driving force for the Fed

In the UK, we love nothing more than talking about the weather – whether it’s too hot or too cold and wet. And when the weather conversation runs dry (pun intended), the next thing we love to talk about is house prices – whether they are going up or about to crash.

There’s been a lot of press coverage on the housing market in recent weeks. Following two years of consistently strong positive performance (up 26.5% between June 2020 and August 2022 according to the Nationwide index), the last couple of months have seen the beginnings of a reversal in house prices, which given the current economic outlook for the UK has sparked speculation of a spectacular crash. With the Bank of England forecasting a two-year recession and consumers facing an unfriendly mix of rising interest rates and inflation, there has been talk of a housing crash to match those seen during the global financial crisis or in the early 1990s.

As large residential mortgage-backed securities (RMBS) investors, we’re clearly focused on what impact all this might have on borrowers’ ability to pay their mortgages, and whether that impact will be severe enough to cause significant rises in arrears, defaults and repossessions. So what are we saying to our friends over the dinner party table when we run out of weather chat?

In this two-part blog we are going to look at what this could mean for mortgage performance. Part one will look at the practical situation of where we are today compared to the past, and then in part two we’ll dive a bit more deeply into the numbers.

To start with, despite the potential doomsayers in the press, in our view today is neither 2007 nor 1989.

In 2007, we had far weaker mortgage regulation allowing self-certified mortgages (now outlawed), far higher loan-to-value ratios (LTVs) of up to 125%, and masses of interest-only loans – generally lower quality, riskier lending. The Mortgage Market Review, finally implemented in 2014, changed all this and placed a greater emphasis on lending standards, with a new focus on affordability and stress tests and significantly reduced lending to impaired credit borrowers.

In the late 1980s, base rates had surged to 15% and even in 2007, rates were around 2.5% higher than today. Meanwhile, unemployment rates were already at relatively high levels of around 7% and 5.25% on those occasions, and rose sharply to highs of around 10.5% and 8.5% respectively.

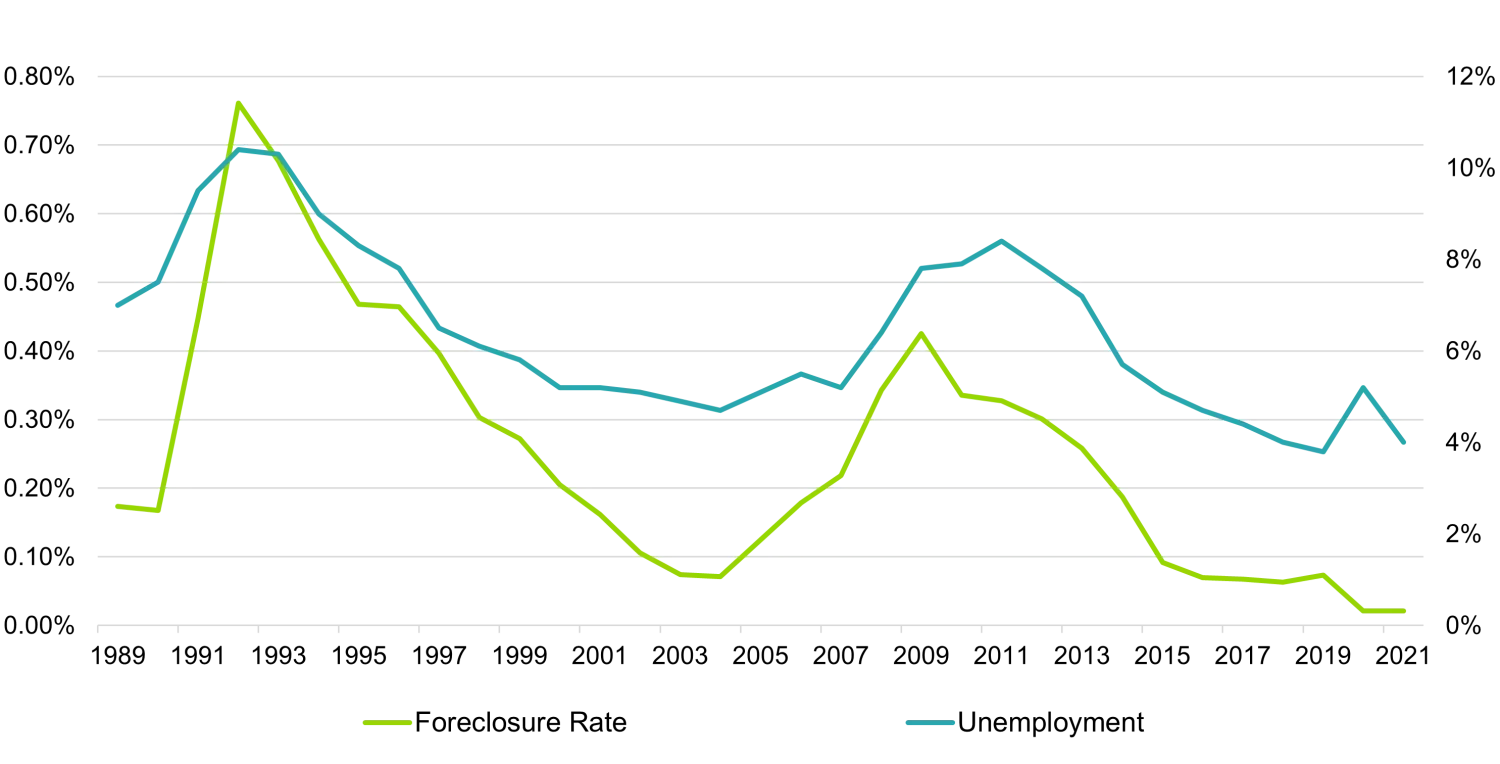

We also know from history that there is a very high degree of correlation between arrears, defaults and unemployment (see the graph below), all of which are at or near historic lows today.

UK Mortgage Market – Historical Performance

Source: UK Finance, Bloomberg, 2 December 2022

There is no doubt that borrowers today are coming under pressure and that’s going to continue for some time. Interest rates have gone up and are expected to rise further, so it is inevitable that there will be an increase in mortgage arrears. But the Bank of England is already commenting that inflation will ease next year and that interest rates may not need to rise as far as the market is predicting.

Furthermore, unlike previous occasions, the UK has a near-record number of job vacancies, a sharply reduced workforce and a higher level of savings following the pandemic. So it is starting from a much better place, even with the pressures of higher energy prices etc. squeezing household finances.

Additionally, lender behaviour has changed. Banks are not under the stress that they were during the global financial crisis, and we learned from the pandemic period that policymakers are keen to promote forbearance rather than foreclosure. With lower risk lending in general, lenders can instead engage with borrowers who fall into arrears to work out affordable payment plans, with repossession then being a measure of last resort. Quite simply, when lenders and borrowers work together to achieve the best outcome – whether that is giving the borrower time to sell the property or coming to an affordable payment arrangement – then that ultimately benefits loan recoveries.

So in conclusion to part one, while some deterioration is inevitable as a result of the economic outlook (house prices may indeed come off by 10% or more), we believe that while rates have further to rise, they are now nearer the peak than the bottom and they certainly won’t reach the levels seen in the 1990s. We expect unemployment will also peak much lower than in either of those periods, and where borrowers do struggle lenders can offer far more help than previously.

This will flow through to the performance of RMBS deals, which, it should be remembered, performed better from a credit point of view through the last downturn than any other credit fixed income market, due to sound structuring and built-in credit protection.

That said, in part two next week we’ll look at some real examples of just how robust we believe these structures are and what it really takes to break them.

Stay up to date with our latest blogs and market insights delivered direct to your inbox.