ESG at TwentyFour – Integration and Engagement

At TwentyFour Asset Management we believe Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) factors can have an influence on the value of our investments.

As fixed income investors our first priority is to ensure we are paid coupons and principal, and we see ESG as a risk to this goal like any other. While TwentyFour’s approach to risk has always been concurrent with ESG principles, we have now formalised this by integrating a robust ESG framework throughout our investment process, with portfolio managers directly responsible for the analysis.

This paper will explain why we consider integration to be the right choice for this firm, how it differs from other approaches to ESG within asset management, and how we believe its application can result in better outcomes for our clients.

With a comprehensive and robust ESG framework in place, it is possible to move a step further and create interesting ‘sustainable’ funds. We define ‘sustainable’ funds as focusing on both the sustainability of the investment and ensuring that the investment is not detrimental to the broader ecosystem that it occupies. For many investors, such funds can allow them to reflect their ethical and societal values.

ESG models

ESG is probably the most talked about and fastest growing discipline in our industry at present. According to the Global Sustainable Investment Alliance’s 2018 report, there are now over $30 trillion of assets being managed under sustainable investment strategies, a 34% increase over the previous two years and up from $5 trillion in 2005. If it is not already, sustainable investing will soon be driven into the mainstream through a combination of asset owner demand, asset manager acceptance, and regulation.

Global Sustainable Investing Assets, 2016-2018 (US $bn)

| Region | 2016 | 2018 |

|---|---|---|

| Europe | 12,040 | 14,075 |

| United States | 8,723 | 11,995 |

| Japan | 474 | 2,180 |

| Canada | 1,086 | 1,699 |

| Australia/New Zealand | 516 | 734 |

| TOTAL | 22,890 | 30,683 |

Source: 2018 Global Sustainable Investment Review1

That said, our industry is still at the beginning of this journey. Having committed a great deal of time and resources to developing our own integrated framework, it is clear to us that while a broad definition of ESG investing is relatively easy, individual firms’ and investors’ interpretations of the concept can vary markedly.

In order to understand how we arrived at what we believe is the optimal ESG investment process for TwentyFour, it is useful to consider the options that we and our peers have available. It should be said that even defining these is not an exact science, so the below describes how we would categorise the various approaches.

Integration

Integration is the most common ESG model adopted by asset managers, going by assets under management. In essence, integrating ESG factors into an investment process should result in a more formal analysis of the ESG risk factors borne by a company or issuer.

Like any other company risk, such as its gearing level or whether future technology is a threat or opportunity to its business, an investor must balance these factors when deciding on the creditworthiness of the company and marry them with a bond’s relative value. Typically an ESG risk will not necessarily mean the bond cannot be considered, rather this depends on if the investor believes the risk in question is reflected in the price of the security. The principle is conceptually simple, though it often causes confusion as many think the model will automatically include some form of exclusion, which is not the case.

Historical statistical studies show that governance issues have been the most significant predictor of performance2, though we can see the influence of environmental and social issues increasing over time as more asset managers begin to take up ESG analysis in whatever form.

Of course, any professional portfolio manager should be taking these risks into account. The advantage of formalising the framework – stitching it into the investment process – is that it proactively ensures these issues are methodically and comprehensively evaluated.

Under the integration model, ESG metrics could account for less than 5% of a bond’s relative value proposition, but this could become 100% if the risks identified are so high that the bond spread could not possibly compensate the investor.

Exclusion

Exclusion, also referred to as negative screening, is a model which seeks to filter out specific countries, companies, sectors or activities deemed to be undesirable investments by asset owners. In talking to investors it is this model that seems to best encapsulate their understanding of ESG investing, or perhaps more accurately, sustainability.

Here the implication for any potential investment will be of an absolute nature, unlike the relative value analysis of an integration approach. Examples would include ruling out involvement with the manufacture of arms, carbon emissions, gambling, alcohol and tobacco. The exclusions desired by different investors can vary significantly, as can their level of conviction, which can make creating a fund using this model fraught with difficulties. Unless asset owners show some degree of flexibility with the ‘exclusion menu’, one can imagine such funds not attracting sufficient inflows, which in aggregate could reduce the potential positive objectives of sustainable investing.

While emotionally the concept of exclusion is attractive, everyone interested in sustainability should at least consider the potential conflicts and complexities we all face. It is possible in some instances to take differing sustainability views on a sector or company depending on your point of view. Do nuclear weapons threaten the world or keep the peace? Is animal testing for potentially life-saving drugs necessary or avoidable? Is running a mine in a less developed country negative because it exploits natural resources, or positive because it delivers local employment and economic development? Is Tesla a ‘good’ company because it produces electric cars, or bad because of its governance and its use of chemicals in car batteries?

We are not saying that negative screening is ineffective. Asset owners have a right to express their beliefs and exclusion is one way for them to do so. In less extreme examples a company’s cost of capital would rise, and this along with investor engagement would hopefully provoke change.

However, the inherent contradictions can produce potentially negative unintended consequences, which we will return to in more detail below.

Impact Investing

The goal of impact investing is to fund assets, companies or sectors aiming for a positive impact on a specific social or environmental issue, such as social housing or renewable energy schemes.

An extension to this is ‘green bonds’, which companies and countries issue to investors looking to fund specific projects, though at times the link between the proceeds raised and their destination can be disappointingly opaque. Currently the supply of ‘impact investing’ assets is relatively small, though it is growing quickly and legislation is being drawn up by the EU to address the explicit link between proceeds and green investments. We believe the principles of the asset-backed securities (ABS) market, where asset pools are well defined and ring-fenced, could offer a possible solution to both of these problems.

Best in Class

Like integration, this model generally requires some form of scoring system, where a fund would seek to invest in companies with relatively good ESG scoring or a score above a predetermined level. The underlying methodology for calculating the relative ESG performance is likely to be, though not necessarily, similar to the methodology used for an integration model. Aside from ensuring the data analysis is correct, the main issue for this model is that by definition the investable universe is reduced, which again introduces the possibility, though not the certainty, of reduced returns and higher volatility. However, it is possible that returns are actually enhanced by focusing on well managed companies from an ESG perspective, and we have seen evidence to support this.

As an investor, for the purpose of encouraging companies to have positive sustainability goals this is an understandably attractive model.

Additional ESG portfolio management tools

As we have said, definitions of the above models are often debated and they can also be comingled, adding an extra potential layer of confusion for the end investor. In addition, there are other tools available to portfolio managers that can be complementary to an ESG investment process without being defined as ‘model’ in themselves.

Engagement

Engagement is an investor’s willingness to actively interact with companies, regulators or government bodies on behalf of their clients. Examples of engagement can range from fundamental governance issues, such as the structure and terms of a bond issue, right through to more general ESG related matters, like the absence or content of a Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) report.

Here equity investors have a natural advantage over fixed income investors, as they can have a tangible impact on company management through voting shares.

That said we, and I’m sure many of our peers, do engage with companies when we feel it is necessary and appropriate. The influence of fixed income investors has increased through time as debt markets have become an ever more important component of companies’ capital structures. TwentyFour as a firm has also spent a lot of time working with regulators, banking authorities and various government bodies, which is an often overlooked aspect of asset manager engagement.

Momentum

In our opinion ‘momentum’ is probably the most underestimated and overlooked concept in the world of ESG investing. Momentum is an assessment of a company’s plan and demonstrable execution towards improving its ESG credentials. Sometimes this will be a general focus on improving all aspects of ESG, and will be reported in the CSR, with measurable targets being preferable. This will likely be of even greater importance to issuers and investors operating in the industries mentioned in our negative screening section above.

Let’s look at an example from the ‘E’ element of ESG. The contribution of carbon emissions to climate change is one of the highest profile topics within ESG, and coal usage for electricity production has been identified as a major source of carbon emissions. Thus it is logical to conclude that coal-based electricity generating companies deserve to be screened out of a portfolio because of their negative externality, carbon emissions. That is simple enough to do. But now let’s assume that all asset owners and investors take this view and refuse to invest – does this get rid of the emissions? We would argue not. In this extreme example, public equity and bond markets shut off sources of capital for the company (or at a minimum significantly increase its funding costs), leaving it unable to carry out infrastructure investments and likely valued at distressed levels. As long as coal usage is not illegal, a private buyer, of any origin, will be able to purchase the asset cheaply and run it for as long as possible with no regard for ESG matters. The non-engagement of capital markets may actually leave the environment in a worse position than before.

UK electricity producer SSE plc is a good example where management recognised the need for change and investors supported their initiatives to bring this about. In 2013 SSE’s coal usage was 20 TWh (Terrawatt hours), or 59% of its production input, and after facing multiple pressures to reduce its coal dependency, the firm made a commitment to substantially reduce this number over time. By 2018 coal usage had fallen to 1.5 TWh, or just 5% of input, by substituting gas, hydro and wind. SSE has stated that their aim is to take coal usage to zero by 2025.

Some important lessons can be drawn from this example. First, companies in sensitive sectors may or may not have choices as to how they respond to societies’ and investors’ increased ESG focus. If you are a producer of tobacco products relying on the addictive properties of nicotine, it is difficult to see how you change that. SSE had a choice – ignore the coal usage issue or deal with it. That SSE chose the latter is commendable, but as investors we have to recognise the practical reality that such a transformation cannot be achieved overnight, and it requires funding.

Ultimately investors may feel they still want to exclude certain countries, companies or sectors for their own personal reasons. We are not saying that there is a right or wrong answer, but in advancing ESG/sustainable principals we believe more desirable outcomes can be achieved by combining exclusion with an intelligent momentum overlay. In some circumstances it may be the companies one may instinctively wish to exclude that require ESG style investments and engagement the most.

We note that some index providers have already established screened indices with no flexibility. In this regard, active ESG management should really add more value than indices in both performance and societal outcomes.

Controversies

Controversies are generally visible signals and can be an important risk indicator. For example, an oil exploration and production company experiencing a major oil leak owing to poor maintenance would likely create negative publicity, litigation, regulation and significant clean-up costs.

The existence of controversies can tell you much about the risk management and ethics of a company. One event may be unavoidable, so the underlying source of the issue is important. More than one event however may indicate a systemic risk is being exposed.

Some caveats

The more you delve into the subject of ESG the more you realise that at a corporate, asset management, regulatory and government level there are complexities and nuances that require hard thought. All parties will undoubtedly make mistakes along the way, but we believe the spirit of the ESG ‘movement’ is correct and can see it is already changing the face of the investing world for the better.

How, for example, do we deal with sovereign issuers from an ESG perspective? This is a question on which we have seen a plethora of views, and some of the more extreme stances would seemingly rule out investing in almost any sovereign debt on ESG grounds. The United States, for example, has the death penalty, possesses nuclear weapons and burns plenty of coal. The question for us is, by utilising an integrated approach, what are the risks and benefits for our investors if we were to take an aggressive stance?

Eliminating certain sovereigns would deny investors a substantial pool of liquidity and one of the most effective risk-off assets in the global markets. Moreover, we are unlikely to influence those governments’ policies. Having said that, given the focus of our strategies, it makes more sense to split the sovereign market into developed and emerging markets. Governments and companies in emerging market countries tend to have starker ESG issues, while generally not being as efficient as ‘risk-off’ assets. Recent concerns over government policy in Turkey have led us to take an extremely cautious view on any asset domiciled in that country, for example.

Similarly, previously we have mentioned the usefulness of CSR reports, which can influence the perception of momentum. Sadly, as investors we have to be aware and cautious of ‘profiling’ by companies. Large firms in less friendly ESG sectors can afford the personnel to write up impressive CSRs, and investors also need to watch out for ‘virtue signalling’ activities, resulting in better profiles than smaller firms who could be superior in terms of their ESG impact. As a result, a smaller company may see abandoning any focus on ESG principles as its optimal strategy for growth, which is not the outcome anyone desires.

Evolution of our thinking

At TwentyFour, we have thought long and hard about how best to approach this important topic on behalf of our investors.

The result is an ESG framework which we feel strikes an effective balance between some of the above approaches, and is applicable to all of our investment strategies and funds.

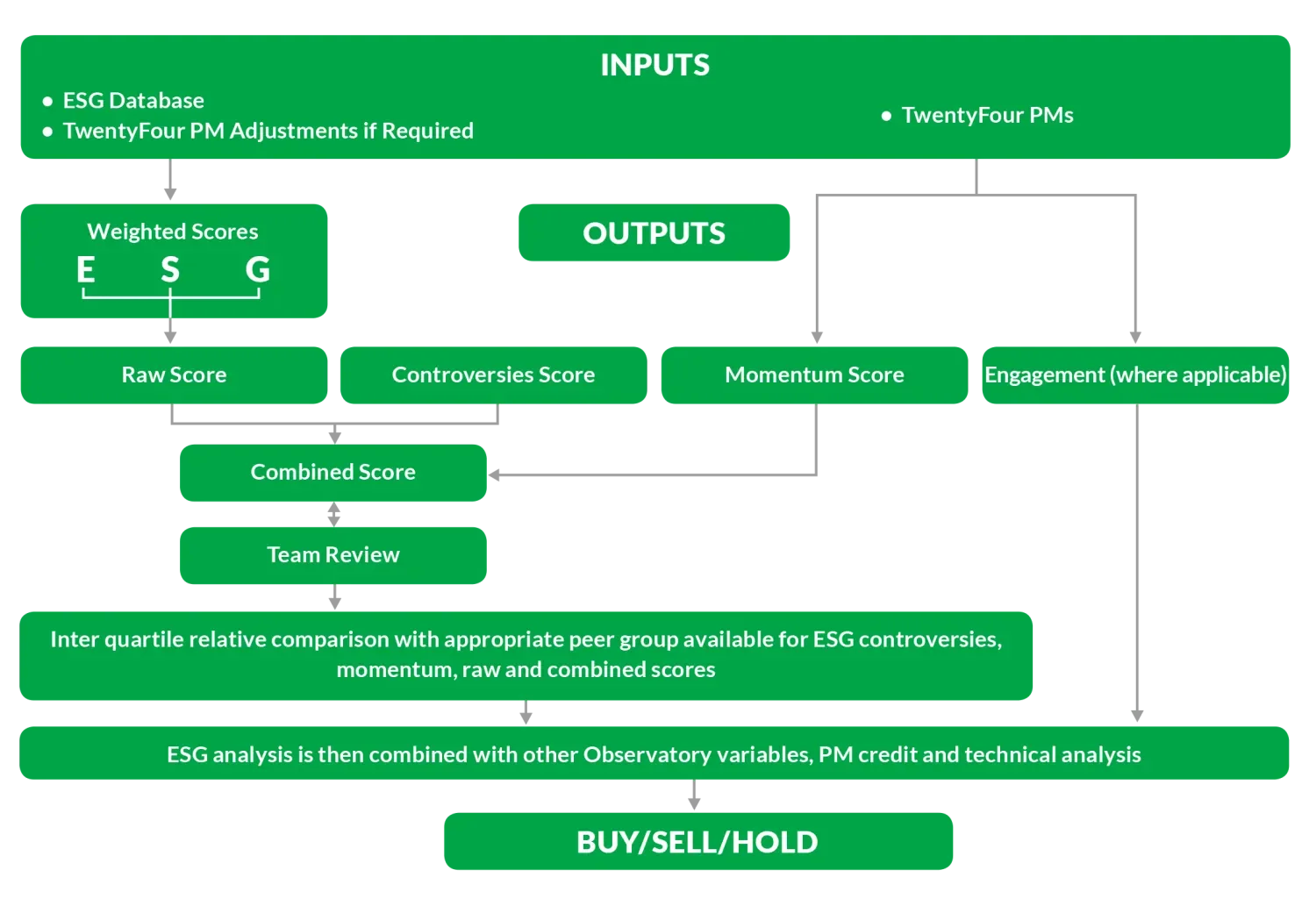

At a high level we have already stated that we believe an integration approach gives the greatest bang for your buck, and is increasingly becoming the ‘new normal’ in our industry. However, we believe it is both possible and desirable to go further. The flowchart below shows how we also incorporate controversies, momentum and engagement in our investment process. At its core the framework is a combination of qualitative and quantitative analysis, which dovetails with the portfolio managers’ overall relative value decision.

By integrating this framework into our existing proprietary Observatory relative value system (using Thomson Reuters data covering over 400 ESG metrics), ESG factors are embedded in a tool already used on a daily basis by the portfolio managers3. This is an important point as we do not feel that a separate ESG team, or outsourcing ESG analysis to a third party, would effectively embed our ESG principles into the investment decision.

ESG factors are only one part of the overall decision to invest, but this methodology gives us a rational defendable starting point. Moreover, having this framework as part of our investment process, we make sure that we actively and consistently incorporate ESG factors into the investment decision.

Conclusion

The ESG environment is rapidly changing and means different things to different people. Above we have outlined the main ESG investment models, along with further factors we believe should be considered when incorporating ESG criteria into investment analysis. Once you scratch the surface of these models, the issues become more nuanced. While the ESG movement is not young, its influence is only now becoming mainstream. We are all subject to these changes and regulation and industry standards are in catch-up mode. Mistakes will undoubtedly be made along the way but we feel the general direction for ESG is positive and its impact on outcomes for investors should be too.

We believe the secret to the effectiveness of our ESG framework – a holistic integration model incorporating controversies, engagement and momentum – lies in its incorporation into our existing relative value model, used daily by all portfolio managers.

For those investors who wish to go further, it is possible for us to create dedicated ‘Sustainable Fixed Interest’ funds by extending our framework to incorporate additional sustainability criteria such as Best in Class and Exclusion. Our research shows such funds can provide investors with an attractive risk-adjusted return profile, and we are actively exploring the opportunities in this area.

1 All 2016 assets converted to US$ at year-end 2015 exchange rates. All 2018 assets converted to US dollars at time of report.

2 Barclays Equity Gilt Study 2017

3 The specialist nature of our ABS strategies means the team models all its investments on a bespoke basis rather than in Observatory, though we maintain the consistency of our integration approach by incorporating the same ESG themes in the ABS modelling.